Rationalizing threat models

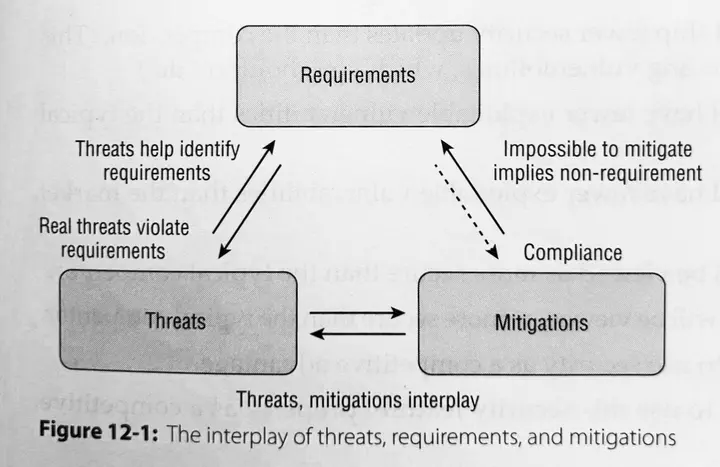

Figure 12-1 from Shostack (2014, p 219)

Figure 12-1 from Shostack (2014, p 219)A recent post on LinkedIn by Adam Shostack began with,

The biggest threat to worms isn’t early birds, it’s rain. The wrong focus for your threat modeling can lead to… I dunno. Rain seems pretty hard to defend against if you’re an earthworm.

which reminded me of a concern I have with how I suspect threat modeling is often practiced. But before I get to my griping, I would like to say that if you have the opportunity to participate in threat modeling training by Adam, take that opportunity.

My initial1 comment on Adam’s post included something like,

Your worm example reminded me of importance of explicitly acknowledging what we can’t defend against instead of creating other rationals for excluding something from the threat model. That is, saying something like, “We exclude rain from our threat model because an attacker powerful enough to control the weather can already own us.” is less helpful than saying, “We exclude rain from our model because we don’t (yet) have the tools to defend against it.”

Our inability to defend against the rain is the real reason our choice of threat model, while the statements about a possible threat actor is a rationale for that decision. This doesn’t mean that the rationale is incorrect, nor does it mean that our choice of threat model is wrong, but I feel that we are far better off if we explicitly acknowledge the real reasons.

In follow-up comments, I shifted to my non-wormy example of perimeter firewalls.

All that’s green does not glitter

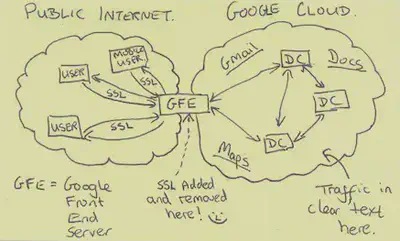

Let’s consider a threat model that lived for about a quarter of a century, as summarized by Ramasamy et al (2011)

The intranet is a trusted network environment for hosting systems, services, and data internal to the enterprise. The opennet is an untrusted network environment (e.g., the Internet) that includes all systems external to the enterprise. [Emphasis added]

In what follows, I will be referring to these as the “green zone” and the ”red zone” respectively. I am ignoring other zones security zones that may have been put in place.

The relevant portion of the accompanying threat model was that network traffic originating inside the green zone was benign, while traffic originating from the red zone may be malicious. It is certainly fair to assume that traffic originating from outside the organization is more likely to be hostile than traffic originating internally, but that hardly means that we shouldn’t worry about threats from within the organizations network.

The Rationale

For those two young to recall the technological environment in which that threat model emerged, there are two important things to note.

Organizations typically had their hosts on premise, including both servers and user workstations. This meant that there was a natural distinction between internal and external networks, with a one or a small number of gateways between the two. Firewalls could be incorporated into those gateways or immediately adjacent to them. The network topology gave us a place to filter and block suspect network traffic. We had a perimeter that could be defended with perimeter firewalls.

Another point about the technological environment is that IT managers and system administrators were wary of updating or upgrading server systems and software. Updates broke things. Client systems often depended on undocumented service behavior.2 Software and systems vendors were often slow to release security updates. Responsible disclosure was not at widely accepted then and so vendors had less incentive to address security vulnerabilities. The consequence of all this is that internal systems riddled with exploitable security vulnerabilities.

In that environment, the practical way to protect servers within the organization was through perimeter firewalls.3 In short, our practical defensive technologies drove our threat model.

Bad rationales raise suspicions

If someone puts forth a rationale for excluding something from a threat model that feels like an excuse, it will lead people to wonder real reason is being concealed. And people will tend to feel that what is being concealed is worse than the excuse itself. That suspicion is particularly unfortunate when the real reason is not something anyone should be embarrassed by.

I offer a vague and brief example of a case where I was put off by what I considered a bad rationale while I expect that the real motivation for a security design decision was perfectly reasonable. I am keeping it vague because my memory of this is not sufficiently reliable to actually call out specific actions.

I recall a browser vendor defending their choice (at the time) to not encrypt user passwords locally for their built-in password manager with something like, “if an attacker gains control of the user’s system they will be able to capture user secrets on the fly, even if those are encrypted at rest." That is certainly a true statement, but fails to recognize that it is much easier for an attacker to obtain read access to a user’s system then it is to maintain the kind of control needed to capture data when a user decrypts. In short, I felt that we were being presented with a bogus threat model to defend a design choice.

The design choice could have been defended. At the time, not few operating systems offered tools for user secret storage, and requiring users to enter a master password to use their browser’s password manager might severely limit uptake in using it. Furthermore it posed a data availability risk to the user if they forgot the password they used to decrypt their password data. Whether I agree with their design choice at the time or not, I fully recognize that it was a reasonable decision.

Their insistence (as I recall, perhaps incorrectly) on what I felt was a bogus threat model argument did not inspire confidence in their security analysis. I assumed that they were being honest when they said silly things about the threats. They would have been less likely to talk themselves into their threat model if they had been willing to explicitly acknowledge to themselves and to others that there choice was based on trade-offs involving usability and the defenses available to them.

Where things go wrong

I absolutely support the practice of putting our defenses where we can. There really isn’t an alternative to that. Relying on perimeter firewalls was a necessity. The problem arises when we let that drive our threat model. It is far better to explicitly acknowledge threats that we can’t defend against than to pretend that those threats don’t exist or don’t matter.

If we come to believe our rationales for excluding something from the threat model

we may find ourselves slower to adopt technologies that come along to address those threats.

After all, we aren’t going to really notice solutions to problems we don’t think we have.

I suspect that green zone thinking delayed transition from from telnet to ssh,

or from

POP3 to

POP3S or of a zero-trust architectures.

I have no evidence to support my suspicion, but my suspicion remains.

Explicit inclusion

I completely concur with Adam Shostack’s position that “Impossible to mitigate implies non-requirement” (Shostack 2014, page 219). There really isn’t any alternative to that position. What I am advocating instead is that we explicitly maintain somewhere in our model things that would be requirements if we could mitigate the threats against them.

My recommendation when constructing a threat model is to to explicitly maintain a category would-be requirements, threats to those would-be requirements, and the reasons why we are not capable of defending against those threats.

Defense capabilities is to be defined in terms of the organization’s resources and capabilities. For example, there may be technologies to defend against a threat, but it may be too expensive for the particularly organization to implement those defenses. There was a period of time when it would have been impossible to wean an organization from Internet Explorer 6, even though upgrades and alternatives were available. There may also be cases where implementing a defense creates other security problems, a measure such as encrypting passwords locally (as in my browser password management example) may create an unacceptable risk data availability. These decisions will need to be made on a case by case basis, looking at users of the system, organizational resources, available technologies, security trade-offs, and costs. The important thing is that these decisions be made honestly and explicitly.

Maintaining such a list and regularly reviewing it will benefit security planning and risk assessment. More importantly it will clarify thinking in that we are no longer inventing unnecessary rationales when we have clear reasons.

My initial comment exceeded the character limit of LinkedIn comments, a fact that nudged me toward writing the post you are now reading. ↩︎

This footnote is too small to contain my rant about systems encouraging the use of malformed data. A large part of why things broke after an update is that malformed input was handled differently, often subtly so, in new versions. Such changes in behavior were often not intended behavior, but a side effect of other changes. ↩︎

Endpoint management of user workstations was also a way to reduce the threat of malicious traffic originating from within the green zone. Anti-virus and frequent re-imaging of user workstations was a regular practice, illustrating that people did know that the green zone wasn’t always trustworthy. ↩︎