In praise of the TAKS

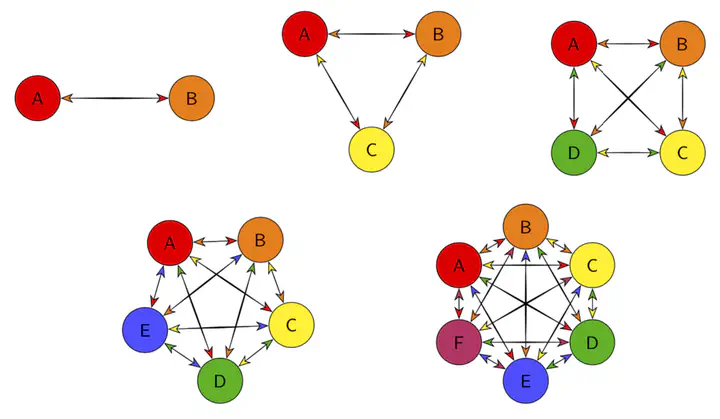

Illustrating n(n-1)/2 growth: Source: https://tex.stackexchange.com/a/493463/31771

Illustrating n(n-1)/2 growth: Source: https://tex.stackexchange.com/a/493463/31771This post was ported from a 2009 article In praise of the TAKS. The TAKS (Texas Assessment of Knowledge and Skills) has long since been replaced, and pretty much all of the details no longer hold, but I still think it is valuable to share my thinking at the time, what I got wrong and what I learned.

Links to resources from the Texas Education Authority have been removed as they are no longer valid.

A few days ago [November 2009] I had an eye-opening experience. I took the 2009 Exit level Math TAKS and have come to the conclusion that it is a far better designed test than I’d anticipated. Below I will explain both my initial pessimism and what impressed me about the test.

Before that let’s get some questions to get out of the way. I took the TAKS as part of a course assignment in my teacher training program. I missed one (out of 60) questions on an easy question due to a silly oversight. I didn’t take the test under normal test taking conditions. On the one hand, I was free to make myself a fresh cup of tea every now and then; on the other hand, I had to put up with the dogs barking at the gardeners. I recommend that anyone – like me – who gripes about Texas standards and teaching to the test should try taking these exit level tests. Past tests are available from the Texas Education Agency for all levels and subjects for which the TAKS is administered.

Why I was pessimistic

I had not expected the TAKS exit level test to be as interesting as it turned out to be. There were several reasons for my pessimism. First was experience with the 3rd, 4th, and 5th grade math TAKS that my child took. They didn’t really seem to involve any problem solving or mathematical reasoning; instead they were about the ability to apply memorized techniques to clear instances. In retrospect this was probably because educators take Piaget too seriously and (incorrectly) believe that grade school kids are incapable of formal reasoning. Whatever the cause, there is a large difference in approach between the grade school TAKS and the exit exam.

The second reason for my pessimism was based on my impression that in high school math education very little time is given to developing mathematical reasoning skills, and most of the time is on specific techniques to solve specific kinds of problems. Real understanding and creative problem solving rarely seemed to be emphasized. I had (incorrectly) attributed this to “teaching to the test”. I had thought what I had disliked about the curriculum was a consequence of the test.

Liking the test

Many problems on the test had multiple ways of getting at the solution. One method would be mindlessly applying the right set of procedures, plugging away at it (typically using a calculator), and eventually coming to an answer. But these problems were also set up as little mathematical puzzles. There was often a key insight which could lead one quickly, easily, and without a calculator to the right answer. Grasping the key to these problems not only saved time, effort, and tedium; but it also was less error prone. Many of the incorrect answer options were exactly the kinds of things one might arrive at for making a minor error (as I did in the question I got wrong). The more steps involved in computing an answer, the more opportunity there is to slip up on one of those common errors. If one had a good grasp of the meaning of the various mathematical concepts then the key was usually available.

Other questions were explicitly about concepts. These questions were not merely testing knowledge of technical vocabulary, but did require an understanding of the concepts to answer correctly. I don’t think I have the skill to come up with questions of that nature, but I can recognize them when I see them.

As a minor anecdote that nicely illustrates how wrong I was about this test there was a question on the test that I had previously claimed would not be on a TAKS test. During my teacher training, I’ve taught some sample lessons to my fellow teachers-in-training. In one of them, I had students develop a model for an instances of n(n - 1)/2 growth. I said at the time that this was an activity that would help them think mathematically but would not be on the TAKS. It was a dig at the TAKS and a completely unfounded one. Imagine my surprise when I hit question 6 on last year’s test and discovered it to be exactly the kind of problem I said would not be on the TAKS.

I’m hoping that I will find time over the next few days to try exit exams in English, Science and Social Studies as well. Although high school teachers are specialists, we should – at a minimum – understand what is being expected of our students in all areas. (Now all I have to do is find someone who will grade the ELA writing sample if I do take that portion of that test.)

Decisions and Revisions

I was wrong in my expectations of the TAKS. Alternatively, I may have been correct in my expectations and wrong about my current evaluation of the TAKS. In either case I’ve been far off the mark at least once. While I certainly don’t like being wrong, I actually enjoy the experience of discovering that I’ve been wrong. It is eye-opening in the best sense. I see things that I previously did not see, and I am forced to reevaluate both the reasoning that led up to the incorrect view and the consequences of that view.

But the big lesson in discovering that I’ve been spectacularly wrong about something is the heightened awareness that other positions that I currently hold firmly may also be wrong. Caveat lector.